SERS vs VERS: Key Differences

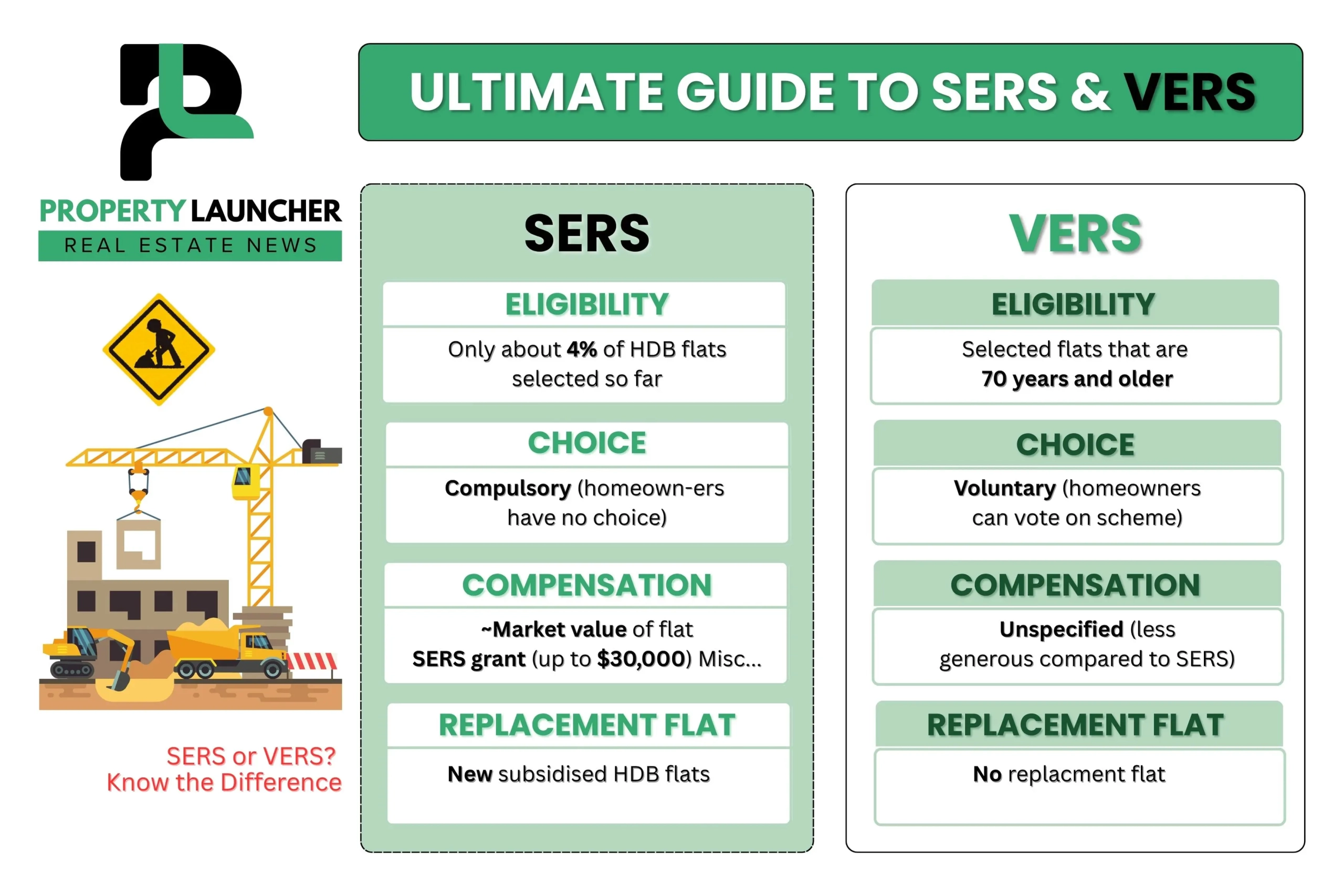

It helps to compare SERS and VERS side by side. Key distinctions include:| Feature | SERS (Selective En Bloc Redevelopment Scheme) | VERS (Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme) |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Government-initiated and compulsory | Government offers, but residents vote to accept |

| Participation | No choice – all owners must sell once selected | Voluntary – precinct needs a strong majority (e.g. 75%) to proceed |

| Age of Flats | Typically ~40–50 years old with high redevelopment potential | ~70 years old (about 30 years lease left) |

| Compensation | Full market value + new replacement flat nearby | Based on remaining lease value – “less generous, less upside” |

| Replacement Option | Guaranteed replacement flat offered | Details still being finalized; likely less extensive |

| Frequency / Likelihood | Very rare (only ~5% of flats ever qualified) | Broader reach, but still selective precincts only |

| Government Role | Picks sites with highest redevelopment potential | Uses staged, precinct-by-precinct renewal over decades |

| Resident Role | No vote or choice – compulsory | Must reach a supermajority for scheme to proceed |

| Financial Upside | Significant – often a windfall for owners | Modest – designed as an “exit plan,” not a jackpot |

| Timeline | Immediate once chosen | First projects only from 2030s onwards |

How VERS Will Work

The Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme is still being fleshed out, but officials have given key clues about its mechanics:Orderly Redevelopment

VERS is designed to “redevelop ageing estates in an orderly manner”. Rather than tearing down an entire town at once, the government will spread projects over decades. Chee noted that many older estates (e.g. Ang Mo Kio, Marine Parade) were built very quickly in the 1970s-80s, so letting them all expire in the 2070s-80s would force relocation of huge numbers of people at once. VERS avoids this by staging renewals over 20–30 years.Resident Vote

When it’s time for an estate to consider VERS, all owners in the precinct will vote. The government has indicated a supermajority (e.g. ~75%) may be required for approval. In practice, this means VERS only happens if a strong majority wants it. If the vote fails, the flats simply stay until lease end (with only routine upgrades).Timeline

Officials aim to finalize VERS policy details by about 2030. After that, the first VERS projects could start “in the first half of the next decade” (i.e. the 2030s). Chee says we won’t see full-scale rollout until the late 2030s, when most older flats hit 70 years. Until then, government agencies will be studying the rules, compensation formulas, and how to relocate different groups fairly.Compensation Details

The exact payout formula is under study. The government has stressed it must be “fair” and sustainable. Expect compensation to be based on remaining lease value (possibly akin to the Lease Buyback Scheme method). That means younger flats are worth more on the schedule, and the last years of the lease add little value. Owners should plan that they may get enough to fund their next home, but not much extra. In fact, the less generous terms mean older owners could face financing gaps.Support for Those Who Opt Out

If a precinct decides not to take VERS (or fails the vote), residents can live out their lease. The government will still maintain those flats. All such estates will receive a second round of Home Improvement Programme (HIP II) around the 60–70 year mark, to keep the blocks safe and livable. The Silver Upgrading Programme (elderly-friendly upgrades) may also apply. However, these do not extend lease length – they just maintain quality. Buyers should not rely on HIP II as an exit strategy, only as a way to keep an aging flat comfortable.VERS is a voluntary, long-term renewal plan with modest compensation. Owners will vote whether to join, and if they do, they relocate earlier than lease-end but without the SERS-style bonanza. It’s crucial for buyers and owners to follow updates, because the fine print (vote threshold, payout rate, relocation assistance) will determine individual outcomes.

Impact on HDB Owners & the Market

“Hope Premium” Vanishes

Without SERS, the anticipation of a lucky en-bloc payout disappears. Property experts note that even in coveted mature areas, a SERS-derived “hope premium” has faded. Buyers who once insisted estates like Tiong Bahru or Queenstown would be next have been proven wrong. We may now see price moderation in these old estates. The lack of any guaranteed SERS means older flats will trade more on location and lease than on speculation of redevelopment.70 as the New 99

Buyers are already treating the 70-year mark as the real cutoffs. If enough precincts take up VERS, 70 years left may become the public’s mental “deadline” for flat value. After that, the clock is effectively ticking on who will need to relocate soon. For owners, this means an older flat will be valued much like a 999-year-freehold would be for a condo — only 70 years of use remain, not 99.Financial Planning Necessity

VERS forces more planning. If you buy an older flat, you must assume you might have to sell it around the 70-year mark of its lease (potentially 20-30 years earlier than 99-year tenure). Property analysts warn that buyers should save extra and plan for that relocation. It affects how much one should pay (knowing you’ll have to rebuy a home later), how much to spend on renovations, and how big an emergency fund is needed. For example, a 40-year-old owner might need to move in 20 years (at age 60) instead of staying till 85. This is a key mindset shift.Not Every Flat Gets VERS

Importantly, no one should assume a VERS offer is guaranteed. The government has stated it won’t require all old flats to go through VERS. It is selective, based on estate viability and resident consensus. That means some flats may see no VERS and simply depreciate with age. This uncertainty is why buyers in old estates may demand a discount. You must ask: if the VERS vote fails or never comes, will I be stuck with a decaying asset? Wise investors will consider that risk when buying.Senior Owners in Focus

Chee Hong Tat pointed out that most VERS candidates will be senior citizens who have lived in their flats for decades. The government aims to protect those who’ve already paid off loans – in fact, it’s screening buyers so “people buy homes that can last them for life”. For elder owners, this means two things: (a) VERS will likely involve older residents, and (b) policies will try to minimize scenarios where seniors outlive their leases. Currently only about 2.5% of HDB buyers fail to have leases beyond their life expectancy, and the government plans to keep that number small as VERS rolls out.It’s likely that VERS will changes the psychological landscape of HDB. Even before the first VERS project, buyers and sellers are adjusting. Many now value older flats for their longevity and location, not for redevelopment profit. Until the framework is public, the mere possibility of a 70-year hard stop alters decision-making. For HDB upgraders, this means being realistic: own an old flat for living or rental, but don’t expect it to finance your retirement with an en-bloc windfall.

Why Consider Private Property?

Extended Lifespan

Private freehold homes (landed houses or some condo plots) effectively have no lease decay – you can rebuild indefinitely. Leasehold condos (typically 99-year) also have remedies: they can enter collective sale (en-bloc) or legally top up their leases when the time comes. As ERA notes, “private property on freehold land can stand as long as physically possible”, since owners can redevelop at will. By comparison, HDB flats are stuck with a finite lease and no owner-driven renewal option. For investors, freehold condos or houses are a way to sidestep lease expiry risk entirely.Owner Control

In a private condominium, owners can choose when to unlock value. If 80% agree, a condo can go en-bloc at market rates, or the collective can approve a lease top-up and redevelopment. HDB owners have no collective sale option – they can only vote on VERS or live on. This gives private owners a strategic advantage: they control if and when to exit, often reaping full capital value. For example, when a private estate was en-bloc sold, owners typically got high compensation because the land could be used commercially. This sort of voluntary deal is not available in HDB, which means private owners can often achieve higher returns when markets are favorable.Stable Resale and Rental Value

Mature condos and landed homes in good locations tend to command steady prices. Even an older condo’s 99-year lease can be extended or renewed, keeping its value high. Rents on such properties also remain strong (if you rent it out). In contrast, HDB flats lose financing and buyer appeal as lease falls below ~60–70 years. Many buyers shy away from flats with short leases, causing prices to drop. Private property tends to have better liquidity, since banks lend more easily against it and there’s a wider buyer base (including foreigners in many cases).Government Support

The authorities are mindful of seniors in private housing too. The Enhanced for Active Seniors (EASE) program – which gives subsidies for grab bars and other ageing-in-place fittings – has been extended to seniors in private homes up to 2028. Condo management councils (MCSTs) will also get new maintenance funding options. This shows that the government is willing to help seniors stay in their private properties comfortably. In effect, living in a private home doesn’t mean losing government support – seniors will also benefit from upgrades, albeit through different channels.Diversification

From an investment standpoint, adding private property means adding a different asset class. HDB prices are strongly tied to lease policy and citizen-only rules, whereas condos follow a broader market. Many Singaporeans are now second-home owners; investing in a condo (or EC) alongside or instead of an HDB can diversify risk. If policies change, one portfolio segment can compensate for the other. Given VERS, having a portion of one’s assets in private property can protect overall wealth.In short, private property offers flexibility and durability that HDB can no longer match under VERS. It often requires more savings up front, but the tradeoff is a longer horizon and greater control. Financial advisers now frequently point out that buyers who can afford it may want to “upgrade out” of HDB rather than rely on public housing schemes. In this sense, VERS tilts the scales toward the private market for long-term investment planning.

What Buyers Should Know

The real estate market is expected to changed drastically over this news and we are already feeling the effects. Here’s what buyers should expect:Plan for 70, Not 99

Treat any older flat as if its effective lifespan is ~70 years. Do not overpay for a flat with only 30–40 years remaining, assuming you’ll enjoy it till 99. Instead, ask yourself if you can finance and find a home at the 70-year point. Adjust loan duration, renovation budgets, and CPF usage accordingly.Check Your Estate’s Likelihood

Research whether your precinct will likely get a VERS offer. Early candidates include original towns with few past redevelopments – for example, Queenstown, Bukit Merah, Toa Payoh, Ang Mo Kio, Bedok, Tampines, Yishun – whose blocks reach 70 years by the late 2030s. If you live in a newer town or one already rehoused, VERS probably won’t come. Buyer demand in older estates will hinge partly on this expectation.Factor VERS Into Valuation

When negotiating price, explicitly factor in the possibility of VERS compensation (or lack thereof). Experts suggest pricing older flats lower to account for their shorter useful life. Don’t assume full lease value or any premium for redevelopment. Likewise, don’t assume the government will subsidize your next home – VERS payouts aim to replace, not to enrich.Don’t Over-Renovate

If your flats is old and might face VERS soon, consider delaying major upgrades. Spending large sums on renovations in an estate that may be voluntarily sold off in 10–20 years could hurt your net outcome.Consider Condo Alternatives

For upgraders, always compare scenarios. If you’re eligible for a private purchase or EC already, run the numbers on how long those properties can last versus an HDB. Remember that private homes can be leased or sold en-bloc to generate value, which provides more exit options.Stay Updated

VERS rules are not yet final. The Ministry of National Development and HDB plan to release frameworks and gather feedback. Keep an eye on announcements to know exact voting thresholds, compensation formulas, and any new relocation grants. This info will critically affect your decision to opt in or out.Leverage Other Schemes

Use existing government support while you can. Silver Upgrading, HIP II, and grants for home loans (like the Enhanced CPF Housing Grant) still apply. These can improve living conditions in older flats without changing the lease clock. But remember: these schemes do not extend your lease – they only enhance your home.By incorporating VERS into your home strategy, you can make more informed choices. Adjust how you value an old flat, strengthen your savings plan, or decide if and when to move to private housing. The transition to VERS doesn’t have to be a shock – proactive planning will smooth the way.

Join The Discussion