Walk down any street in Singapore, and the question echoes between coffee shops and show flats alike, “Can anyone still afford to buy a home?”

Behind that anxiety lies the complex web of Singapore housing cooling measures, policies designed to keep the dream of homeownership alive, yet often accused of making it harder to reach.

For over a decade, these measures have balanced the razor’s edge between stability and suppression. But in 2026, with global inflation, climbing interest rates, and shifting investor appetite, the debate has reignited:

Are these cooling measures protecting Singaporeans, or quietly freezing opportunity?

Let’s look deeper into how these policies work with Singapore’s Property Launcher, whom they protect, and whether they’re steering the housing market toward stability or stagnation.

Philosophy Behind Singapore Housing Cooling Measures: A Nation Guarding Its Future

Housing in Singapore isn’t just about property; it’s about national identity. More than 90.8% of residents own their homes — not by chance, but through deliberate long-term planning anchored by the URA Master Plan in Singapore.

Since the 2000s, rapid urbanization and foreign investment sent property prices soaring. The government’s answer was a series of housing cooling measures, a moral and financial safeguard against the chaos of speculative booms.

The Core Principles

- Protect Singaporeans: Ensure Singaporeans can afford a home despite rising wealth & foreign interest. Incentives are given to Singaporean to get government housing.

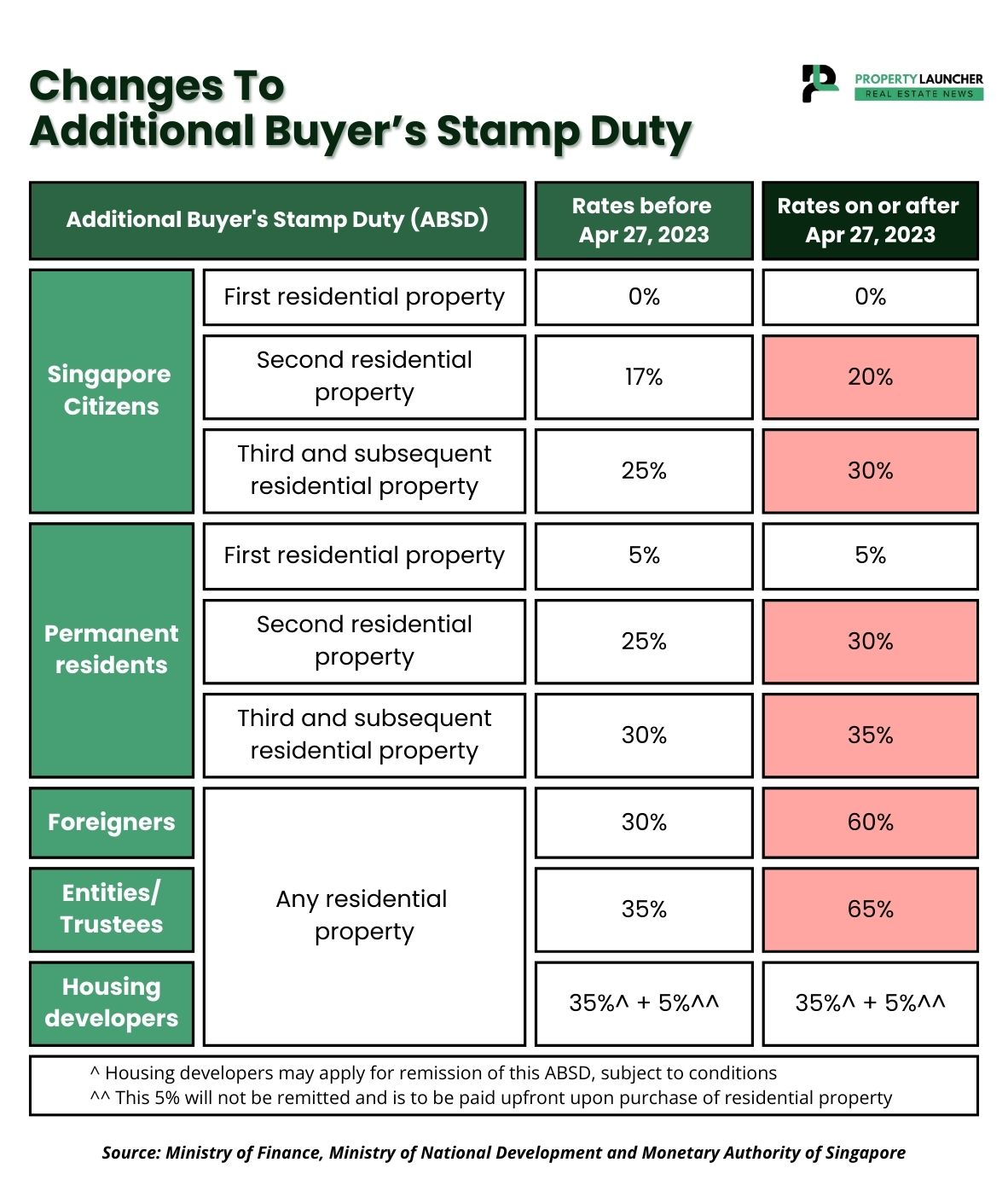

- Prevent Speculation: Discourage short-term flipping that drives artificial price spikes. ABSD (Additional Buyer Stamp Duty) and Prime-Plus Model recently introduced in 2023.

- Sustain Long-Term Stability: Build resilience in a market easily swayed by global capital.

These principles birthed policies that have since become famous or infamous across the Singapore property market. The long-term benefit we know is that Singapore property remains one of the safe-haven assets that Singaporeans, PRs, and foreigners love to invest in.

Anatomy of the Cooling System: The Policies That Move the Market

Imagine Singapore’s property market like a big classroom. If too many people rush to buy the “best seat,” things get messy, prices go up, and some students can’t get a place. The government uses special rules, such as a “cooling system,” to maintain fairness and calm.

These rules tell people:

- Don’t rush.

- Don’t buy too many.

- Don’t treat homes like toys or trading cards.

Let’s look at the different parts of this “cooling system.”

Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD)

ABSD is like an extra fee you must pay when you buy a house. This rule helps:

- Make the market calmer and more steady

- Stop too many investors from buying everything up

- Keep homes affordable for families living in Singapore

For example:

If someone from another country wants to buy a home in Singapore, they must pay a very high fee (60%). Why so high? Because Singapore wants homes to be mainly for people who live here, not for people who just want to buy and sell to make money.

Think of the property market like recess time. If everyone runs for the chicken rice stall at the same time:

- People push and shove

- Some stronger kids take all the swings

- The smaller kids can’t play

Without rules, rich investors could buy many houses at once, pushing prices up so high that ordinary families can’t afford a home. So the government steps in like a teacher:

- “Slow down!”

- “Take turns.”

- “Don’t block others from using the playground.”

These rules don’t stop people from buying homes. They simply make sure everyone has a fair chance.

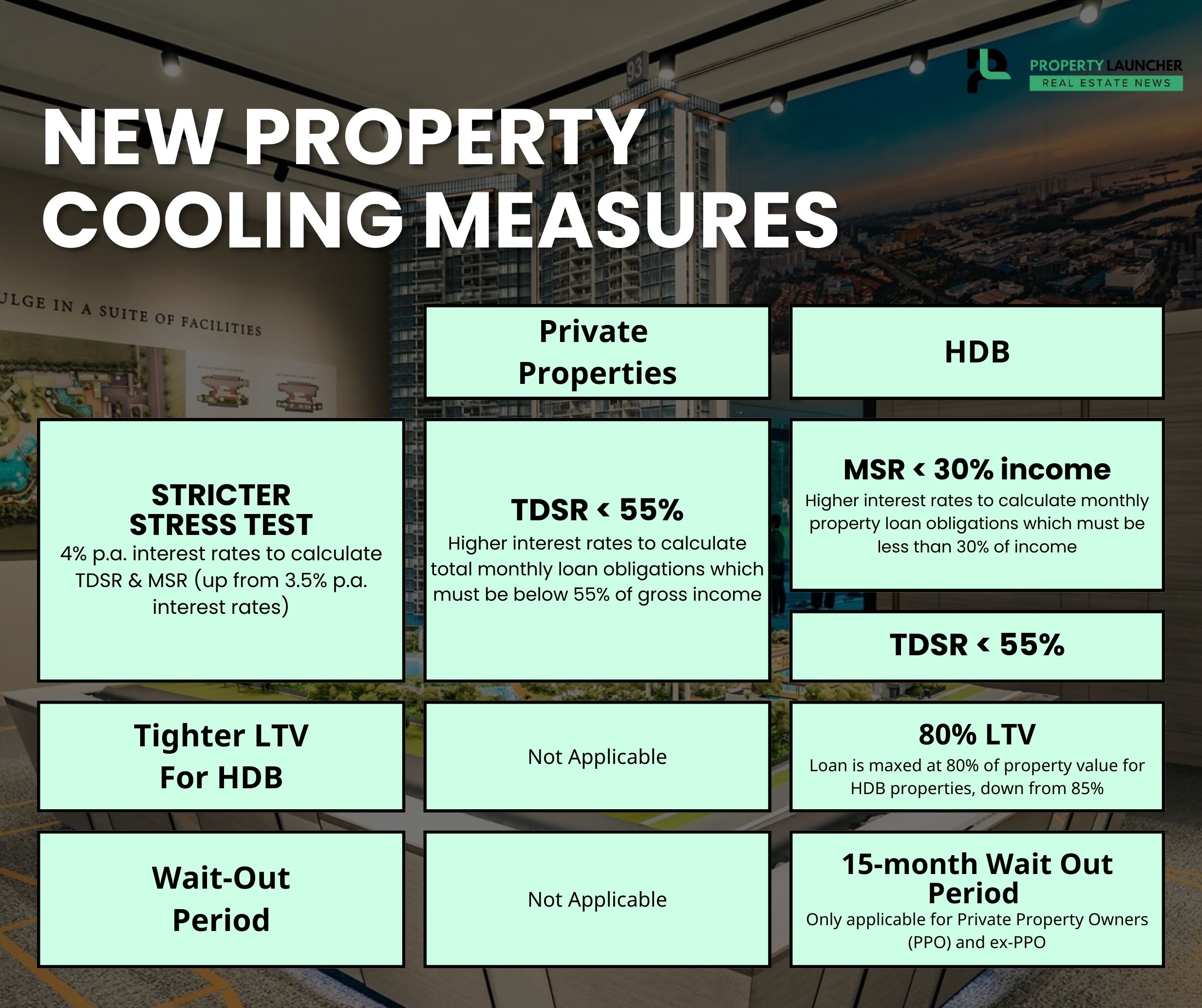

Loan-to-Value (LTV) and Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR)

Since the 2008 Financial Crisis, the Singapore government has been strict when it comes to borrowing and leveraging of funds. These are important real estate rules that decide how much money you can borrow from the bank.

Think of it like this:

If you want to buy a big toy but don’t have enough pocket money, your parents might say:

“You can borrow some, but not too much. We don’t want you to struggle later.”

That’s exactly what LTV and TDSR do:

- LTV: how much the bank can lend you

- TDSR: how much of your monthly income you can use to repay loans

These rules help families not borrow more than they can handle, so they don’t get into money trouble. But it also means some families must save longer before they can buy a home. As real estate investor or buyer, knowing how to maximise TDSR is crucially important in building up your real estate portfolio; that’s what some buyers forgo buying a car to reduce bad debt.

Seller’s Stamp Duty (SSD) and Minimum Occupation Period (MOP)

These rules stop people from flipping houses too quickly, like trading Pokémon cards the same day just to make profit.

- SSD: If you sell too quickly, you pay a penalty

- MOP: If you buy an HDB flat, you must live in it for a few years before selling it

For HDB flats, owners must live in the home for a required number of years (commonly 5 years) before they are allowed to sell the flat or rent out the entire unit. This ensures that people buy HDB homes to live in them, not to treat them as investment tools. Together, SSD and MOP make homes feel like real homes, not gambling chips in a fast-money game.

2025: A Year of Tightrope Balancing

The housing picture in 2025 is not about turning the dial hard in one direction — it’s more like walking carefully on a tightrope, steadying balance because global uncertainty is high, and many families and investors are nervous.

- The authorities continue to keep most cooling rules firmly in place, rather than loosening them, signaling a cautious approach in uncertain times.

- According to official statements, the government is “not averse” to further tightening, if needed, to avoid a housing bubble.

What’s Still Firm in 2025

- ABSD remains high. The extra tax on additional properties and on foreigners buying property is still applied, making speculative purchases expensive.

- Credit rules stay tight. Limits on how much buyers can borrow (LTV) and how much debt they can carry (TDSR) remain in force. This keeps leverage under control.

- Public housing support and supply remain part of the plan. The government continues to rely on more public housing — flats for local families — to help absorb demand.

The message the government sends is straightforward: “Better to cool than to collapse.” They’d rather maintain stability than risk a sharp, uncontrolled fall in property values that could hurt many homeowners.

What It Means for People: Young Couples, Upgraders, & Investors

Not everyone views the steady hand the same way.

For couples or younger buyers hoping to upgrade from public housing to private condos, the high-tax and tight-loan environment can feel discouraging. The dream of moving to a plush condo can seem more distant.

At the same time, investors — especially those looking for quick flips — are finding the climate tough. The risk and cost are high; profits are harder to guarantee.

But for longer-term investors, 2025 is a test of patience. With speculation less attractive, success now depends on careful timing, good data, and a long-term view, not quick trades.

For Investors: The 2025 Rules of Engagement

Even under these cooling measures, there’s still room to invest — but the playbook has changed:

Foreign demand remains weak, but many consider Singapore property a safe, stable long-term store of value, which still attracts cash-rich buyers in less volume than before. The Straits Times+1

Rental demand stays solid. With expatriates, transient workers, and Singaporeans who can’t buy yet, rental could remain a stable source of return — especially if flips are no longer viable.

Capital gains will be slower. Flash gains from flipping are rare now — the market rewards patience, not speculation. Investors may shift strategy. More may lean toward buying smaller units or rental-oriented properties (rather than luxury condos for quick resale). Or they may wait for good timing — maybe when policies ease, or supply tightens.

The Bigger Picture: Global Eyes on Singapore

Many people around the world now watch how Singapore handles its housing market and some view it as a kind of “textbook example” of how to manage property cycles with care.

While no country has fully copied the Singapore HDB model, some, like Indonesia, have adapted similar public housing policies. Others, such as Hong Kong and Seoul, have expressed interest or are considering taking inspiration from it, though they face challenges due to differences in political, social, and economic contexts.

Observers point out that Singapore doesn’t rely on luck or boom-and-bust cycles. Instead, the government continually adjusts rules and supply to keep prices stable, demand manageable, and risk low. This deliberate balancing act is something few countries have pulled off with consistent success.

The reason it’s manageable: when speculation picks up too much, authorities have tools such as extra taxes (on foreign buyers or multiple-property buyers), tighter loan rules, or stricter resale rules. When everyday homebuyers struggle, they can release more public housing flats or offer subsidies — helping families afford a home without pushing prices sky-high.

This constant recalibration gives Singapore a reputation for “engineered stability.” It doesn’t promise runaway gains, but it promises that housing markets stay broadly accessible and safe even when global interest rates wobble or when investors act without caution.

What’s Next: 2026 Outlook

Here’s what many analysts expect — and what people should watch out for — as we move into 2026 and the next few years:

| What could happen | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| Modest but steady price growth in private homes (perhaps 3–5% annually) | Means buying remains possible and stable, less boom-bust risk than in many markets. |

| HDB resale growth may slow or flatten, especially if more new flats come online and “MOP-ready” flats increase supply. | Could ease pressure on public-housing buyers; may narrow gap between resale and new or private homes. |

| Interest rates and global economic conditions will play a big role. If global rates ease and loan rates drop, demand might pick up again. | Could give buyers more breathing room; help first-timers or upgraders. |

| New incentives or new housing policies (e.g. for green buildings, different living configurations, more public flats), sometimes used if demand shifts or affordability becomes an issue. Some analysts expect the government to remain ready with new policy tweaks if needed. | Could further shape what “affordable” or “desirable” means, and who benefits most. |

| Shifts in buyer sentiment, more cautious, more selective. With rapid flipping harder, many may look for long-term value: maybe smaller units, rental-oriented properties, or stable living rather than quick profit. | Could reshape demand, balancing between investors and “end-users” (families, long-term residents). |

Overall, while nothing is guaranteed, most experts agree the market is likely to stay healthy, moderate, and more predictable than many elsewhere in the world.

Discover Singapore’s latest launches in CCR, RCR, OCR and EC—complete with live price lists, PSF ranges, floor plans and daily refreshes.

Discover Singapore’s latest launches in CCR, RCR, OCR and EC—complete with live price lists, PSF ranges, floor plans and daily refreshes.

Join The Discussion